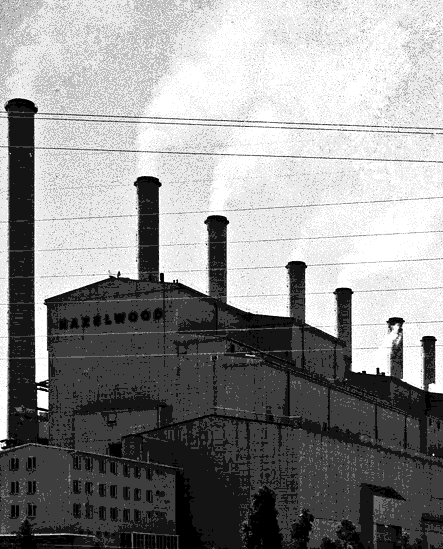

Hazelwood's last days outlined

The Hazelwood coal-fired power plant is shutting down.

The Hazelwood coal-fired power plant is shutting down.

Around 700 people will be out of work from March next year, after Hazelwood’s French owner, ENGIE, said the 1,600 megawatt power station was no longer economically viable.

Hazelwood employees will leave their jobs with an average payout of $330,000, after the company put aside $150 million for redundancies and leave of the plant's workers, many of whom have worked there for decades.

CFMEU Victoria mining and energy president Trevor Williams described the closure as “another kick in the guts for the Latrobe Valley”.

The Greens sought to take credit for the closure of the plant in a Facebook post just hours after workers were told the plant would shut.

“Together we did it! Australia’s dirtiest power station will close!” the Facebook post said.

“It’s time to move beyond coal and ensure a just transition for workers and communities.”

The CFMEU criticised the Greens for the tone of its celebrations, labelling it ‘inappropriate’ given that hundreds of Victorian residents’ futures had been cast into doubt.

Greens leader Senator Richard Di Natale said the Turnbull government’s climate change policy was inappropriate.

“The Turnbull government knew for years that Hazelwood, Australia’s dirtiest power plant, was going to shut down and did absolutely nothing to mitigate the hundreds of job losses that have unfortunately come about as a result,” Senator Di Natale said.

“To my mind, failing to develop either a coherent climate or industries policy to cope with these eminently foreseeable events is what’s inappropriate here.”

ENGIE chief executive in Australia, Alex Keisser, said the mine will be turned into a lake.

About 250 people are expected to get work managing the site’s rehabilitation, some of which will be former Hazelwood workers while others will be sub-contracted.

“There've been multiple inquiries on the mine in the last two years, the conclusion of the inquiry that's just occurred was to transform the mine in all a full lake or a partial lake,” Mr Keisser said.

“What we intend to do is work with the regulator and the community in order to do exactly that, which is to transform the mine into an element that can be given back to the community.”

Head of environmental engineering at Monash University, Dr Gavin Mudd, says the level of rehabilitation required for such a large facility is almost unprecedented in Australia.

“We just haven't closed mines this big in Australia, because typically they just keep going, so we haven't really had to deal with these issues yet,” he told the ABC.

“There are theoretical models and there's a few examples that are much smaller, such as the Collie open cut coal mines over in Western Australia.

“From a hydrology point of view they've been able to fill up as lakes, but they've got very significant problems with both saline lakes and acid mine drainage that's coming off the mine sites and is basically making the water quality worse.

“The volume of the pit would be something in the order of 700 million cubic metres — that's a huge hole to work out what to do with.

“We need to understand that sometimes these things may take hundreds of years before a lake like that actually reaches the surface and indeed if it ever can.

“Will the water quality be acceptable for recreational purposes in the pit?

“At least in the Hunter Valley of the Bowen Basin it would be quite straight forward to push all the overburden back into the remaining hole and fill it up so that there is no lake.

“We have a huge amount of coal for a very low amount of over burden and that means that you can never backfill a pit.”

Print

Print