Lizards in live evolution

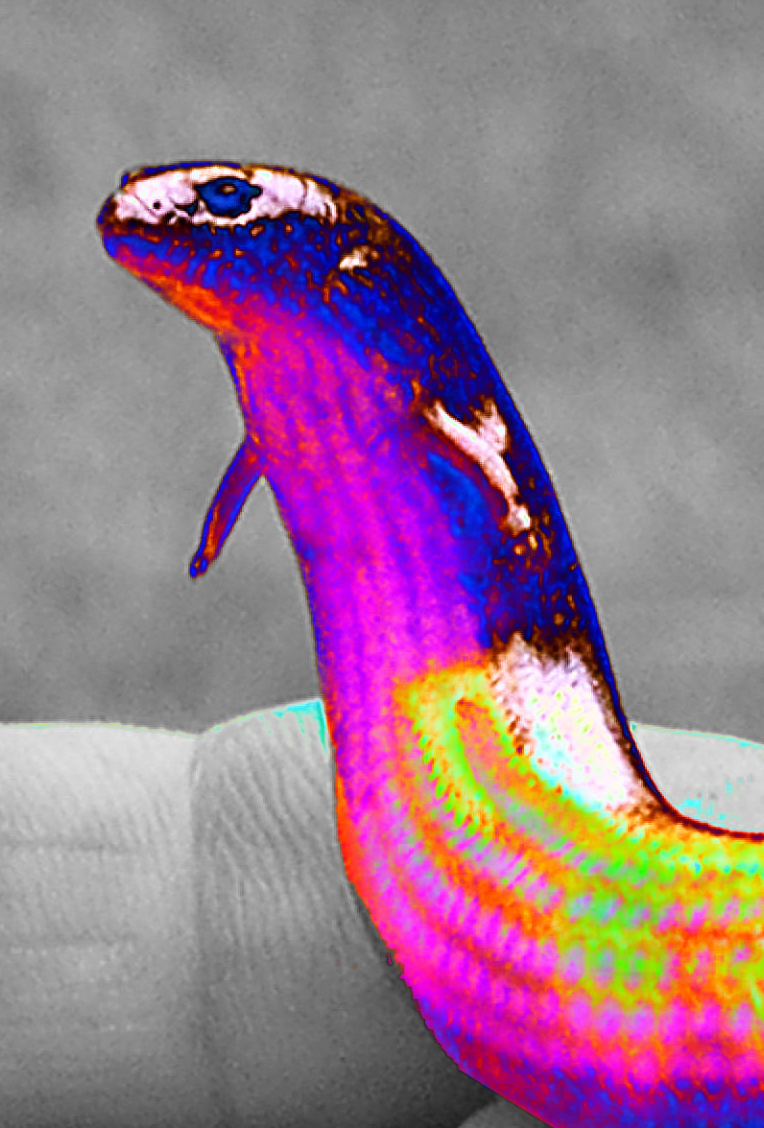

There is a type of small Australian lizard that sits in an interesting evolutionary middle ground.

There is a type of small Australian lizard that sits in an interesting evolutionary middle ground.

Our vertebrate ancestors all laid eggs, but over years of evolution, the phenomenon of live birth has emerged.

Those that lay eggs are called “oviparous”, while animals that carry embryos internally are known as “viviparous”.

Going from egg-laying to live birth requires massive physiological changes – scrapping the ability to produce structures like a hard outer shell and life-giving yolk, and developing the ability to supply oxygen and water to a growing embryo.

It is a big overhaul, but it must be important, because the evolution of live birth has occurred at least 121 times in independent groups of reptiles.

An exceptionally small group of species can do both egg-laying and live birth. Out of more than 6,500 different species of lizard worldwide, just three species are known to exhibit “bimodal reproduction”. Two of those species live in Australia.

There is a research group at the University of Sydney that studies Australia’s bimodally reproductive three-toed skink.

In a surprising geographic twist, the three-toed skink gives live birth in northern NSW, but communities of exactly the same species living near Sydney prefer to lay eggs.

Normally, only a few genes need to be expressed for an egg-laying species to go from having an empty uterus to one that holds an egg. But for a species to give live birth, they usually require thousands of genetic changes to help support the developing baby, changes that help it provide oxygen and water, and a whole new immune system to keep the baby safe.

The bimodal three-toed skink S. equalis has come up with a hybrid method – undergoing thousands of genetic changes that allow it to produce either an egg or an embryo. Its genetic changes mean it carries an embryo (either for an egg or live birth) much longer than similar species do. This means that its eggs hatch about 5 days after being laid, much faster than the 35 days it takes an ordinary skink egg to hatch.

The research team that discovered the genes behind bimodal birth says it show that three-toed skinks are a fascinating evolutionary intermediate. S. equalis uses gene expression for egg-laying that is closer to the changes for live-bearing skinks, which in some cases have led the skink to lay eggs and give birth to a live baby in a single pregnancy.

The experts say the findings suggest that evolutionary reversals – going from live birth back to laying eggs – may be more common that previously thought, especially for species like S. equalis that have only recently developed live birth.

Print

Print