PFAS block risks chips

The world is cracking down on PFAS chemicals, but the toxic materials are vital for computer chip production.

The world is cracking down on PFAS chemicals, but the toxic materials are vital for computer chip production.

Bans on per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) have set alarm bells ringing in the chip-making industry.

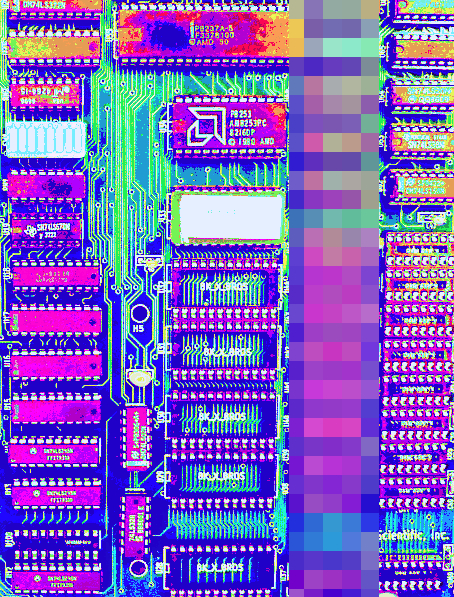

PFAS chemicals are used in the production of microchips, smartphones, electric vehicles, and other high-tech products.

However, policymakers are increasingly concerned about the health and environmental risks associated with these “forever chemicals” that do not easily break down in the environment. The chemicals have been linked to fertility issues, liver disease, reduced foetal growth, and an increased risk of cancer in humans.

The European Union (EU) has initiated a public consultation on proposals to ban up to 10,000 chemicals, including PFAS, with a transition period of 13.5 years for the chip industry.

If implemented, it would be the widest restriction on chemicals in history.

Some chemical companies are not waiting for regulations and have announced plans to halt PFAS production due to the risks and mounting lawsuits. 3M, a major player in the industry, aims to stop PFAS production by 2025.

The potential bans and production halts have caused concern among top chipmakers and their suppliers, including Intel, TSMC, BASF, and others.

The companies fear disruptions in chip production and supply chain due to the scarcity of PFAS.

With no suitable alternatives available in the market, the chip industry faces a challenging task of finding new chemicals and overhauling production processes across various sectors.

PFAS chemicals are highly resistant to water, oil, and heat, making them essential for chipmakers in guaranteeing the purity and quality of manufacturing processes.

However, the strong bonds in PFAS molecules make them persistent in the environment and accumulate in human organs, posing severe health risks.

Studies have shown PFAS presence in the blood of 99 per cent of Americans and unsafe levels in drinking water and soil.

Experts say that European PFAS-related health costs could reach billions of euros annually, while the cost of reversing the environmental and health damage could amount to trillions of euros.

Replacing PFAS is a complex task, especially for fluoropolymers, a type of hard plastic derived from PFAS. These fluoropolymers are critical for chipmaking processes, including coatings and chemical-resistant parts.

The semiconductor sector alone consumes 45 per cent of the fluoropolymers used in the electronics industry.

While some companies argue for differentiated regulations that allow critical PFAS variants, environmental experts warn that previous attempts at differentiation have resulted in the substitution of one harmful chemical with another.

They believe that regulating PFAS will incentivise the development of safer alternatives.

Chip and chemical companies claim to be working on alternatives, but implementing them will take time. Major players like Apple have committed to phasing out PFAS in the long term, opening up opportunities for new companies that are developing PFAS-free solutions.

Industry figures say customers may have to prepare for the initial higher costs associated with the new products, and that alternative chemicals will likely take more than a decade to be widely adopted.

Print

Print